Last month, an Ontario Health official warned that reaching 900 COVID-19 patients in its intensive care units (ICU) could trigger a triage protocol, in which some of the province’s oldest and sickest patients would not receive the highest level of care available. Ontario only narrowly averted this life-or-death scenario.

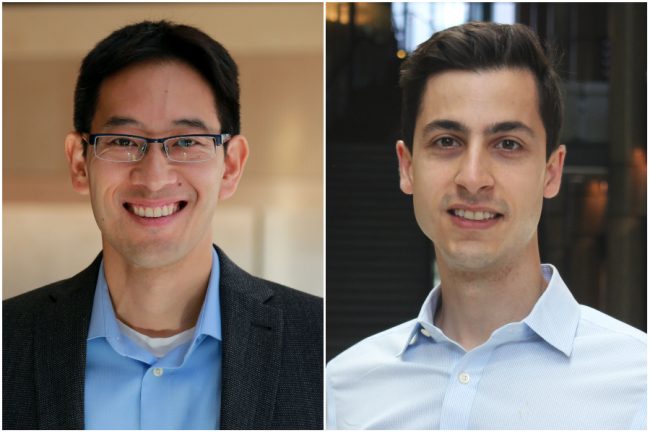

The pandemic has shone a light on the difficult decisions that must be made in order to manage hospital capacity, quality of care and patient outcomes. Helping to inform these tough calls are health-care optimization experts, such as Professors Timothy Chan (MIE), Canada Research Chair in Novel Optimization and Analytics in Health and Director, Centre for Healthcare Engineering, and Vahid Sarhangian (MIE), Associate Director, Centre for Healthcare Engineering.

Chan and Sarhangian recently spoke to writer Liz Do to share their insights on the ICU capacity issues in Ontario, and how they’re helping to optimize hospital operations during and after the pandemic.

We’re seeing very high numbers of hospital admissions in Ontario due to the pandemic. Explain the role of optimization modelling in addressing patient flow.

Sarhangian: Hospitals have limited capacity and resources, so broadly speaking the role of modelling and optimization is to help better match the scarce resources with demand, in order to reduce waiting times for access to care and improve patient outcomes.

Chan: Regarding what’s happening right now in ICUs, there will be some hospitals that are in much higher demand. So, the number of patients coming into the hospitals may be more than what they can handle. And then there will be hospitals elsewhere in the province that have the opposite situation. The role of optimization modelling, and what we’ve been doing with some of the province’s decision makers, is to inform patient transfers and help balance the load.

What’s involved in deciding patient transfers, such as who should be transferred and to where?

Chan: Transferring patients from one hospital to another is a very complex process. What we’ve been focusing on is just one piece of the puzzle — we’re analyzing occupancy level projections and hospital resources to see how to best move patients around. But the overall process is much more involved: you must look at how far away you’re moving the patient, the timing and the right care. There’s a lot of care-coordination involved.

Sarhangian: Generally, hospitals operate close to or even sometimes above capacity and are difficult and expensive to staff. COVID-19 has led to an increase in demand for ward and ICU beds and staff. To cope with this increase in demand, the options are to either add more beds and staff, which is expensive and impractical in a short period of time, or reduce the demand from other sources by cancelling elective surgeries.

Transferring patients allows for balancing the occupancy levels across hospitals in the short term but still requires lots of coordination and could potentially affect the health outcomes of the patients being transferred. So, making patient transfer decisions require managing multiple complex trade-offs.

Tell me about your collaboration. How is it helping to improve patient transfers in the province?

Sarhangian: Our work has focused on developing a decision-support tool that leverages data and analytical methods such as queueing theory, simulation and optimization to find patient transfers that minimize the number of days hospitals spend above certain occupancy levels — for example, 95 percent — during a surge of COVID-19 cases.

We’re focusing on this objective because it’s been well-established that high occupancy levels at hospitals can lead to poor outcomes and higher mortality rates for the patients. Our tool only recommends the number of patients to be transferred from one hospital to another. Deciding which patients should be transferred is left to the clinicians.

What is the status of this work? Are you currently working with hospitals in the Greater Toronto Area?

Chan: We’ve been collaborating with clinicians who provide data that we’re using for our modelling, and folks at Ontario Health who are supporting the decision-making process. We’ve presented our work to decision makers who oversee recommending how many patients should move from where to where.

Note that even after COVID-19 passes, this work will be helpful in terms of recovery and addressing all the surgical cases that are backlogged.

Even as experts in your field, do the challenges of COVID-19 and its effect on our health-care system surprise you?

Sarhangian: From a research perspective, it’s been interesting to see how COVID-19 has introduced new and challenging problems related to management of patient flow. Hospital capacity strain is not a new problem though. So, it’s been surprising to see how the pandemic has highlighted its importance and the necessity for new solutions to address it.

Chan: What I find surprising is that at a global level, everyone has become so engaged and has redirected their efforts towards COVID-19. I think it’s helped highlight the existing issues that everyone knew were there, these systemic issues that really need to be fixed. I hope we realize now that we need to implement changes so that when the next pandemic comes, we’re prepared.

– This story was originally published on the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering News Site on May 17, 2021 by Liz Do