Professor Kevin Golovin (MIE) analyzed 12 different face masks to investigate connections between discomfort and protection.

Wearing a face mask, when combined with other protective measures, has been shown to help slow the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19. But there are still many misconceptions about the relationship between a mask’s level of protection and its comfort.

Professor Kevin Golovin (MIE) — along with his Durable Repellent Engineered Advanced Material (DREAM) Laboratory research team — recently completed a comfort assessment of face masks to determine if masks that offer a greater degree of protection, such as N95 respirators, lead to additional discomfort for the wearer.

The group found the most important factors in selecting a comfortable face mask include size and fit, and that masks that offer more protection do not cause a decrease in comfort.

Writer Lynsey Mellon spoke with Golovin about the findings, presented in a paper recently published in the open access journal PLOS ONE.

Why did the DREAM Laboratory decide to conduct this experiment?

We know wearing a face mask helps to minimize exposure to and stop the spread of COVID-19. We’ve also learned that multi-layer masks offer the best protection. However the most common reason individuals give for not wearing a mask, or choosing to wear a mask that offers less protection, is comfort. We wanted to validate if there was actually a correlation between face mask discomfort and the level of protection the mask offers. To do so, we collaborated with the Apparel Innovation Centre in Calgary, as well as textile scientists at The University of British Columbia.

What kind of discomfort do people experience when wearing a mask?

Most of the discomfort people experience when wearing a face mask is thermophysiological, meaning the mask interferes with our body’s ability to regulate its temperature through heat transfer. The hot air we exhale increases the temperature and moisture levels in the areas covered by the mask. This can lead to the wearer feeling too warm, a damp feeling on the mask or the mask clinging to the skin, which some wearers may find difficult to tolerate for long stretches of time.

What type of face masks did your team investigate in this study?

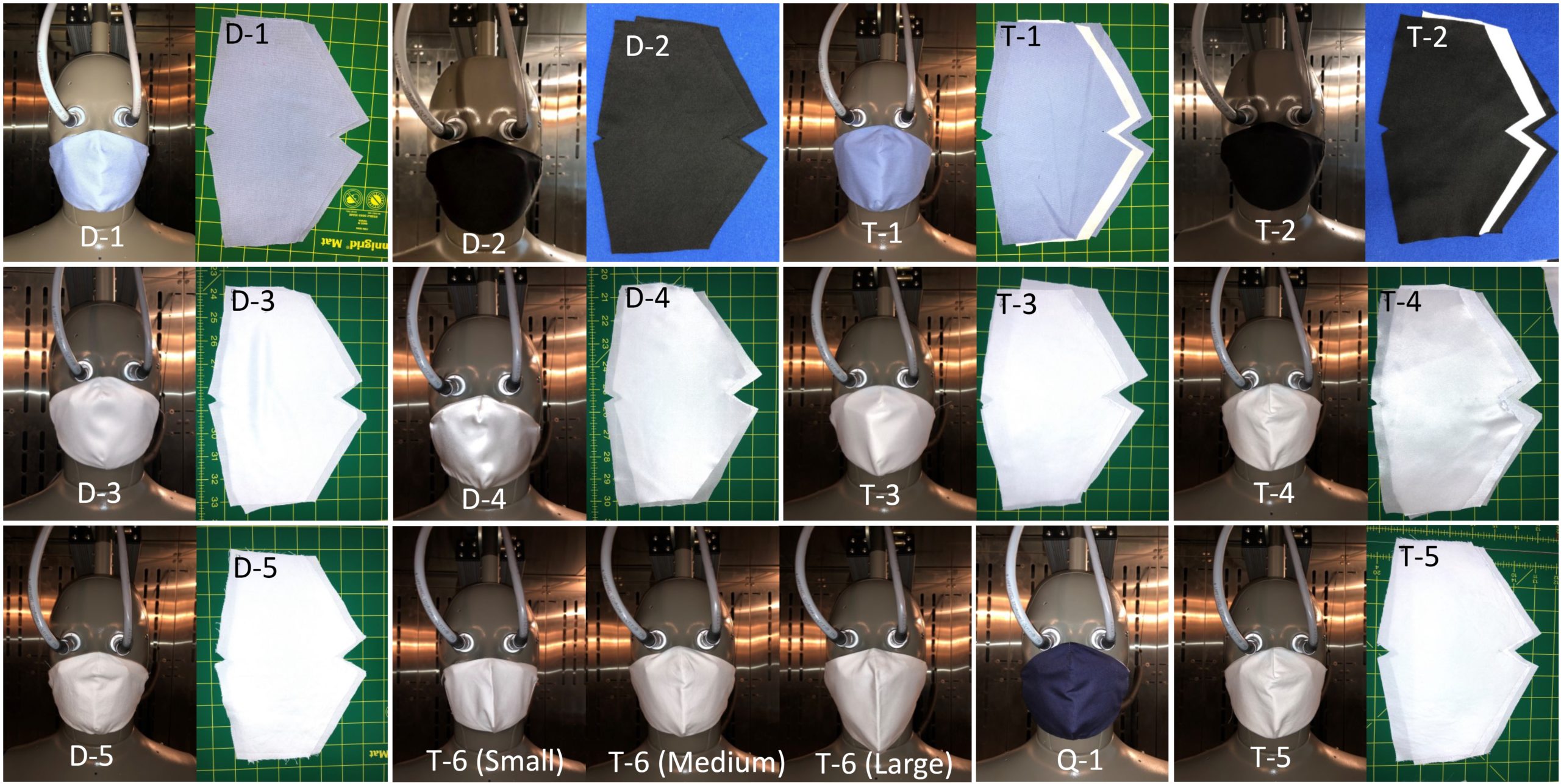

We constructed 12 different layered face masks in three sizes using a variety of commercially available fabrics such as silk, polyester/cotton blends, cotton and polypropylene. We also studied the effect of N95 filters as well as antimicrobial and water repellent finishes on some of the fabrics. We wanted to systematically compare enhanced-protection masks, such as an N95, with those that offer less protection, such as a two-layer fabric mask.

How were the tests performed?

To test the various face masks that we constructed, we used a sweating thermal manikin, Newton, that was fitted with heaters, temperature sensors and sweating nozzles. The thermal manikin is modelled after the average adult male.

Each of the masks was fitted onto the manikin and then we assessed how the thermophysiological comfort levels were impacted by the mask size, fit and fabric properties.

Can you give us a summary of your findings?

Our research showed that wearing any face mask affects the body’s ability to transfer heat and moisture in the areas covered by the mask, meaning all face masks are somewhat uncomfortable. However, we found that adding the additional layers of protection, such as an N95-grade filter or an anti-viral coating, had a statistically insignificant effect on heat and moisture transfer.

These results show that added layers of protection do not cause any significant decrease in thermophysiological comfort and so individuals should opt for a mask that offers the highest level of protection, and ensure it is the proper size and fit for their face to maximize both protection and comfort. Contrary to popular belief, safer masks are not more uncomfortable.

-Published April 8, 2022 by Lynsey Mellon, lynsey@mie.utoronto.ca